Arab uprisings: from street politics to global solidarities

Rather than a presumed “awakening” and contrary to a form of “presentism”, which consists on the vision of an ever changing and “eternal Middle East” (Davis, 2009); the Arab uprisings were a continuation of protests that have broken out in the region since nearly thirty years (Gelvin, 2016: 334). Indeed, before the 2011 uprisings, the Arab world had gone through harsh economic times being affected by the 2008 global recession, characterized by youth unemployment, the decline of public welfare functions, fiscal crisis, etc. Perceived[1] rise in inequalities and absence of social justice – as a consequence of economic liberalization interwoven with cronyism and the rollback of the state – exacerbated social discontent (Cammet, 2015: 4). Besides economic factors, other determinants can explain the uprisings[2]. However, in this essay, rather than focusing on why, I look into how the massive uprisings could have been possible. While some scholars adopt exclusively macro-perspectives that describe the movements as “waves” (Gelvin, 2016: 336), it seems more appropriate to combine a multi-level analysis in order to apprehend the passage from individual to collective dynamics (El Chazli, 2015). By so doing, we shun the orientalist bias that tends either to focus only on elites or to label the uprisings as an “awakening” of homogenous Arab masses which would finally embrace Western values and constitute a sort of contemporary French Revolution. Actually, I will refer to Asef Bayat’s concept of nonmovements[5] as the starting point of a multi-level analysis. In order to do so, I will focus on how ordinary people have constituted powerful nonmovements able to challenge neoliberal logics (Bayat, 2013). Afterwards, I explore the process of articulation of those nonmovements with the emergence of organized social movements through trans-Arab solidarities. Finally, I discuss the role of globalization in the construction of a revolutionary universe of meaning that fostered common identities and transnational solidarities.

Streets politics: the power of local nonmovements

In order to understand the overall logic of the protests, we must analyse every level as “being inextricably tied to broader questions of capitalism in the Middle East” (Veltmeyer, 2011: 185; cited by Agathangelou, 2011: 555). The “Economic Reform and Structural Adjustment” programs implemented in the Middle East during the 1980’s sparked pervasive neoliberal logics that have impacted local socio-economic dynamics. In other words, this economic shift constituted a “Washington consensus-style economic reforms [that] exacerbated inequalities and made life more difficult for the poor” (Gause, 2011: 86). This economic reorientation gave birth to what Bayat has called “neoliberal cities”: a market-driven urbanity “where capital rules, the affluent enjoy, and the subaltern are entrapped” (Bayat, 2012: 116).

How did these new logics operate at the local level and how could they produce the conditions of possibility for later mass protests? To answer this question, we must firstly focus on the local dynamics at work. In fact, the spatial dimension (Choukri, 2009) is crucial when analyzing social movements as space constitutes “both a resource and one of the elements at stake, [which] can potentially provoke sociability and politicization” (Bennani-Chraïbi, 2012: 790). Therefore, only by departing from a micro-level perspective that takes into account the spatial dimension can one determine how socio-economic dynamics affected ordinary people and how these dynamics sparked collective action in the cities of the Middle East affected by neoliberal policies.

Beforehand, Bayat asserts that the “neoliberal city” constitutes an urban opportunity structure that he entitled the city-inside-out. What does this mean? In this neo-city, subalterns were compelled to massively step into the public spaces and streets (ibid.: 114-115) and outdoor economies became the rule. As a result of decades of harsh economic measures that resulted in massive unemployment, contributed to the emergence of an informal economic sector, in which workers were not any more covered by any kind of labor laws, compelled to eke out a living by selling any imaginable kind of products in the streets.

Hence, poors and lower classes encroached the streets, stretching their heavy presence into public spaces (ibid.: 114) while, simultaneously, the wealthier city dwellers commenced to enclose themselves into exclusive areas (ibid.). In other words, these dialectical processes of “inside-outing” and “enclosure” contributed to what some scholars have depicted as the death of the cities and their substitution by mere urban spaces (ibid.: 116). Henceforth, these urban spaces governed by neoliberal logics have given way to new dynamics in the cities’ streets of the Middle East, where subaltern populations started dominating the streets by their presence. Consequently, the “neo-liberal cities”, as urban spaces governed by neoliberal logics, have given way to new opportunities for subaltern populations.

However, the authoritarian national contexts constituted a constraint for any organized movements. This absence of political opportunity structures restrained large-scale shared practices to mere “collective actions of non collective actors”, that is nonmovements (ibid.: 121). Moreover, the “death” of the cities and their transformation, as we have seen, into mere urban spaces, could be perceived as a symptom of the widespread neoliberal logics characterized by a predominant individualism in social interactions.

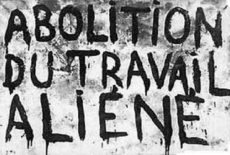

Nonetheless, as Bayat puts it, unintentionally, the peculiar streets of the neoliberal-cities implied “new dynamics of publicness” that provided potential opportunities for subaltern struggles (ibid.: 119). Hence, the streets became “crucial arenas” for what he called “street politics” and “political street”, which have involved power struggles over the control of the public sphere and order (ibid.). Thereupon, the power of nonmovements rested on their capacity to shape the political agenda by means of simultaneous and similar deeds as well as through shared political opinions (ibid.: 124). In fact, the streets became political when nonmovements of ordinary people started sharing grievances and opinions (ibid.: 120). When this happened, “daily encroachments, by multitudes of people have virtually transformed the cities of the Middle East” (ibid.: 121-122). Consequently, when shared political messages unify non-movements, they constitute a powerful agency in times of constraint (authoritarian context), even when devoid of any structural organization.

As Bayat argues, we assist at the “art of presence” of subalterns who may achieve survival by a sort of countermovement of repossession – in the sense of Polanyi (1944) – as a response to their status of dispossessed in the neoliberal city. Therefore, the city-inside-out has become the “spatial expression of subaltern politics in the current neoliberal urbanity” (ibid.: 125).

Arab nationalism as a framing permitting an organized collective action

If Bouazizi’s self-immolation was a symptom of the general discontent about the dispossession of neoliberal cities, how can we explain that millions of Middle Easterners went out into the street demanding Khobz, Huriya; Karama[3]? Streets and squares implied a collective behavior that derived from a common frame from which individuals would develop shared schemes to interpret the world and label events through common strategies (Goffman, 1974). In fact, « successful collective actions depend on how movement issues are framed” (Rabrenovic, 2011: 245); to the extent that, individuals would enter mass movements once they had successfully operated the necessary process of “frame alignment” with their fellows (Snow, 1986: 464).

Despite post-arabism claims, this common frame could be found in Arab nationalism as a common matrix from which nonmovements could align their framing in order to interpret the world. Valbjørn and Bank also argue that Middle East regional politics show at the societal level a “prevalent popular framing that takes place within an Arab nationalist narrative” (Valbjørn and Bank, 2011: 8). The Arab world, they assert, is a cultural space in which information, ideas, and opinions resonate with little regard for state frontiers and contribute to a strong sense of supra-state community (ibid.: 8-10). Hence, according to the authors, a new form of Arab nationalism is taking place, characterized by a “societal Political Arabism in an Arab-Islamic public” (Valbjørn and Bank, 2011: 14). If the first wave of pan-Arabism, promoted by Nasser, was a secular ideological project, the revival of Arab nationalism involves religious ties. Both authors argue that this new phenomenon is related to two intertwined dynamics. First, the authoritarian contexts compelled “discontented citizens” to address regional critics rather than directly geared towards their own rulers, as it was more safe. This contributed to the formation of a sense of political community. A second decisive factor was the information revolution, which has been fostered by trans-Arab media (ibid.: 13). If the first observation is less accurate in the context of the Arab revolts, since the people addressed their protests directly to their own dictators; the role of the media has definitely been crucial. Indeed, al-Jazeera for instance, produced a common Arab narrative that “paved the way for the emergence of a « new Arab public sphere’”(Lynch, 2006; cited by Valbjørn and Bank, 2011: 14).

As well as the aforementioned authors, Gause claims that there still exists a “cross-border pan-Arabism” characterized by a common political identity (Gause, 2011: 88). This author underlines a significant difference, which lies on the very leaderless quality, in the absence of a new Nasser, of the contemporary pan-Arabism (ibid.). This conception ties up with the idea previously described of non-collective actors bound by an Arabic common identity which could – to some extent – justify the Arab labellization of the uprisings. Indeed, despite the non-movement characteristic at its origin, the Arab upheavals have shown that “what happens in one Arab state can affect others in unanticipated and powerful ways” (ibid.: 89). In this sense, Arab nationalism seems to have played a decisive role at the regional level. However, is this ideology the unique explanation that permits to comprehend how mass protests have been made possible in the region?

From Arab solidarities to transnational solidarities: a constructivist approach

Tahrir square and other urban spaces in the Middle East arose as decisive forums where people became active assemblers of meaning and narratives, sharing discursive practices[4] that modelled new identities. Hanafi describes the emergence of these new identities through two main actors in the uprisings, namely the youth and the labor movement, whose new political subjectivity has been labeled by Hanafi as “reflexive individualism”, as opposed to the neoliberal logic of methodological individualism previously described (Hanafi, 2012: 199). This reflexive individualism became a “source of unification” and sectarian or religious slogans unfit the “radical re-imagining” – in the sense of Castoriadis – of a new ideology that promoted a non-violent mode of action (ibid.: 203).

The movements adopted “a revolutionary language and political symbols that have referred to democracy, social justice and dignity rather than religious slogans” (ibid.: 208).These messages echoed worldwide, since social and mass media opened new possibilities for symbolic interactions between local, national and international movements. Hence, social activists promoted transnational ties by “articulating common transnational agendas” to address common issues (Rabrenovic, 2011: 205). “International happenings, ideas, norms, products and encounters with the cultures, agents and structures of globalization”, all contributed to the formation of new forms of socializations that conducted towards a “global ethos” (Sadiki, 2016: 325).

Occupy London Tent, 25 May 2011. (Source: Cyber.Harvard.edu. Workshop: Understanding the New Wave of Social Cooperation: A Triangulation of the Arab Revolutions, European Mobilizations and the American Occupy Movement).

Sadiki talks about “peoplehood” as “the product of travelling discourses that contribute to determine collective subjectivities and social practices” (ibid.: 327). This phenomenon of peoplehood involved three embedded dynamics: “a bottom-up mobilization capacity in physical spaces”; “people-driven dynamics that embrace the slogan for the people!”; “local and global demonstrations embedding national and transnational solidarities” such as Occupy Wall Street, Indignados, etc (ibid.: 327). To be sure, this empowered the Arab uprisings beyond Arab nationalism, since “street politics” should not be “unconnected with global trends” (ibid.: 324).

Conclusion

Far from the idea of “exceptionalism” that tends to homogenize a so-called “Arab mind” that needs “authoritarian rulers to keep the various artificial nation-states of the region together” (Davis, 2009), we should actually question the validity of the label Arab uprisings. If trans-Arab medias stimulated a new form of Arab nationalism that could have fostered regional forms of solidarities, the Arab dimension appears inaccurate, mainly for two reasons: first, not every predominantly Arab country has seen emerging upheavals; and second, their grievances and discursive practices were shared with wider movements. In fact, “the display of people power in the public squares challenges orientalist stereotypes of Arabs as passive, invisible and resistant to the values of freedom” (Gelvin, 2016: 332). Structural approaches of social movements “downplayed the role of emotions, perceptions and individual choices” (Rabrenovic, 2011: 252) and as we have seen, it appears important to look into the level of “street politics”, as spatial structures that “shape, galvanize, and accommodate insurgent sentiments and solidarities” (Bayat, 2010: 162). Though, we must articulate these local phenomena with global dynamics since Arab masses are interconnected with the world as they “respond and learn from other protests, movements and revolts” (Sadiki, 2016: 331). Indeed, the Arab uprisings shared their grievances with other social movements across the world as they “spoke language of human and democratic rights and social and economic justice” (Gelvin, 2016: 334).

[1] The use of « perceived » here relies on the fact that the rise of inequalities did not start in 2010, but already in the 80’s with the implementation in the region of the structural adjustment programs commanded by the International Monetary Fund.

[2] Determinants of the uprisings: Neoliberalism; Demography; World food prices; Weak state/representative institutions (Boussaid, 2016)

[3] Bread (for justice in the redistribution of the nation wealth); Freedom (of speech, political organisation, self-determination, and from repression of the state); and Dignity (a “descent state” treating people as human beings and as Charles Taylor puts it, politics of recognition: of identities, sexualities, and all ways of life) (Kanie, 2016)

[4] Diverse slogans and symbols in Egypt, see http://www.arabmediasociety.com/?article=850

[5] The concept of nonmovements refers to « the collective actions of noncollective actors; they embody shared practices of large numbers of ordinary people whose fragmented but similar activities trigger much social change, even though these practices are rarely guided by an ideology or recognizable leaderships and organizations » (Bayat, 2010: 14).

Bibliography

– AGATHANGELOU, Anna M. and SOGUK, Nevzat (2011), “Rocking the Kasbah: Insurrectional Politics, the “Arab Streets”, and Global Revolution in the 21st Century”, Globalizations, 8:5, pp. 551-558.

– BAYAT, Asef (2010), Life as Politics: How Ordinary People Change the Middle East, Amsterdam: Stanford Amsterdam University Press.

– BENNANI-CHRAÏBI, Mounia, FILLIEULE, Olivier (2012), “Pour une sociologie des situations révolutionnaires”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 62, no. 5, pp. 767-796.

– CAMMETT, Melani [et al.] (2015), A Political Economy of The Middle East, Boulder: Westview Press.

– CHOUKRI Hmed (2009), “Espace géographique et mouvements sociaux”, in O. Fillieule, L. Mathieu, C. Péchu (eds), Dictionnaire des mouvements sociaux, pp. 220-227.

– GELVIN, James L. (2016), The Modern Middle East: a History, NewYork/Oxford: Oxford University Press.

– GOFFMAN, Erving (1974), Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience, Boston: Harvard University Press.

– KURZMAN, Charles(2002), “Bin Laden and Other Thoroughly Modern Muslims” in Sage journals, vol. 1 no. 4, pp. 13-20.

– LYNCH, Marc (2006), Voices of the New Arab Public – Iraq, Al-Jazeera, and Middle East Politics Today, New York: Columbia University Press.

– PETRAS, James and VELTMEYER, Henry (2011), Beyond Neoliberalism: A World to Win, Burlington : Ashgate Publishing Company.

– Polanyi, Karl (1944), The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. New York: Farrar & Rinehart.

– RABRENOVIC, Gordana (2011), “15. Urban Social Movements” in DAVIS, Jonathan, Imbroscio, David (eds), Theories of Urban Politics, London: Sage. Manquent pages

– SADIKI, Larbi (2016), “The Arab Spring: The People in International Relations” in FAWCETT, Louise, International Relations of The Middle East, New York: Oxford University Press.

– SNOW, David A. [et al.] (1986), « Frame Alignment Processes, Micromobilization, and Movement Participation », American Sociological Review, vol. 51, no. 4, pp. 464-81.

– VALBJØRN Morten and BANK André (2012), “The New Arab Cold War: rediscovering the Arab dimension of Middle East regional politics” in Review of International Studies, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 3–24.

Websites

– BAYAT, Asef, Egypt, and the post-Islamist Middle East. Open Democracy, February 8, 2011. https://www.opendemocracy.net/asef-bayat/egypt-and-post-islamist-middle-east, 20 October 2016

– DAVIS, Eric, “10 Conceptual Sins in Analyzing Middle East Politics”, in The New Middle East Blog, http://new-middle-east.blogspot.nl/2009/01/10-conceptual-sins-in-analyzing-middle.html, 2009 (18 October 2016).

Conferences

– El CHAZLI, Youssef: « The Individual in Political Events», International Conference on September 15, 2015, Lausanne: University of Lausanne.

Vous devez être connecté pour poster un commentaire.